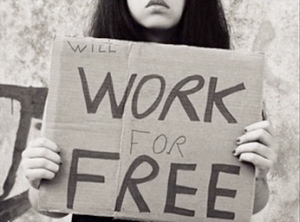

As our guest blogger Lori wrote, “Get yourself out there” is a major job market cliché, but how far can you go without being exploited? Unpaid internships are still popular in some UK sectors, but everyone should draw the line between work experience and exploitation, writes Carolina Are

According to campaigning website Intern Aware, “Unpaid internships are exploitative, exclusive and unfair. By asking people to work without pay, employers exclude those with talent, ambition and drive who cannot afford to work for free.”

Sometimes however you might fear that turning down an opportunity because it’s unpaid could damage your career. However, Chris Wheal, chair of the National Union of Journalists’ Professional Training Committee, thinks differently.

He told the Press Gazette last year: “Potential future employers can see the difference between paid-for work and freebie sites and have little time or respect for those who place so little value on their own work that they give it away for free.”

He added: “Not paying students for their work is exploitation. These companies pay their staff salaries, their office rent and their webhosting bills. They pay for their telephones and their computers. They should be paying for content too.”

Jasmine Patel on Intern Aware said that internships are “a rite of passage” for a lot of young graduates. She said: “There is no doubt that some of us found our internships to be a fun and exciting way to learn more about an organisation, but for many of us, not getting paid caused us real issues.

“It seemed very unfair to those of us whose internships lasted more than a week or two, and involved contributing to the success of an organisation, not to receive acknowledgment or pay for that contribution.”

According to Intern Aware, to be entitled to the national minimum wage you must be a ‘worker’. This means someone who works under a contract of employment or any other contract where they work personally for someone.

Intern Aware shared some very useful ways to find out if you’re a worker include:

- Whether there is an obligation on you to accept work or services from the company and an obligation on the company to provide that work, i.e. a mutuality of obligation between both parties

- The extent to which you are required to undertake work personally

- Whether you are rewarded for your work

- The extent to which you are ‘under the control’ of the organisation.

- The length of the internship.

Indeed, according to Intern Aware Internships of 1-2 weeks do not generally enable an intern to do any significant work for a company and therefore it is less likely they will be a worker.

However if an internship is for a longer period it is likely that the work the intern does will be of increasing value to the company and there is more chance of them being a worker.

This means you should then draw the line between useful and important work experience, which might help you realise if you ‘fit’ in a company’s team and if it’s the area you’d like to work in, and internships, where you’re actually contributing to a company’s turnout and should therefore be paid.

You can find the Government’s guidelines about internships here.

Picture by: brightfutures.co.uk